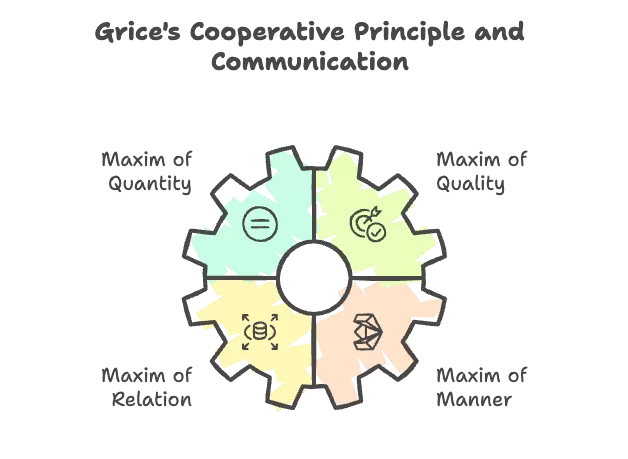

Communication is more than just exchanging words; it’s about effectively conveying meaning so that both the speaker and listener understand each other. Linguist Paul Grice introduced the Cooperative Principle to explain how people engage in meaningful conversations. This principle is guided by four fundamental maxims: Quantity, Quality, Relation, and Manner.

While these maxims describe typical conversational expectations, it’s essential to recognise that neurodivergent individuals, including autistic people, may engage with communication differently. Understanding these differences can help foster better conversations across neurotypes.

The Cooperative Principle: What Is It?

Grice’s Cooperative Principle states that individuals communicate in a way expected to be truthful, informative, relevant, and clear. This principle assumes that speakers are working together in a conversation, rather than misleading or confusing one another.

To ensure effective communication, Grice outlined four conversational maxims that people typically follow—consciously or unconsciously. However, these maxims are based on allistic (non-autistic) communication norms and may not fully account for autistic communication styles, which can prioritise precision, directness, and depth differently from allistic expectations.

The Four Maxims of Conversation and Neurodivergent Perspectives

1. Maxim of Quantity: Be Informative

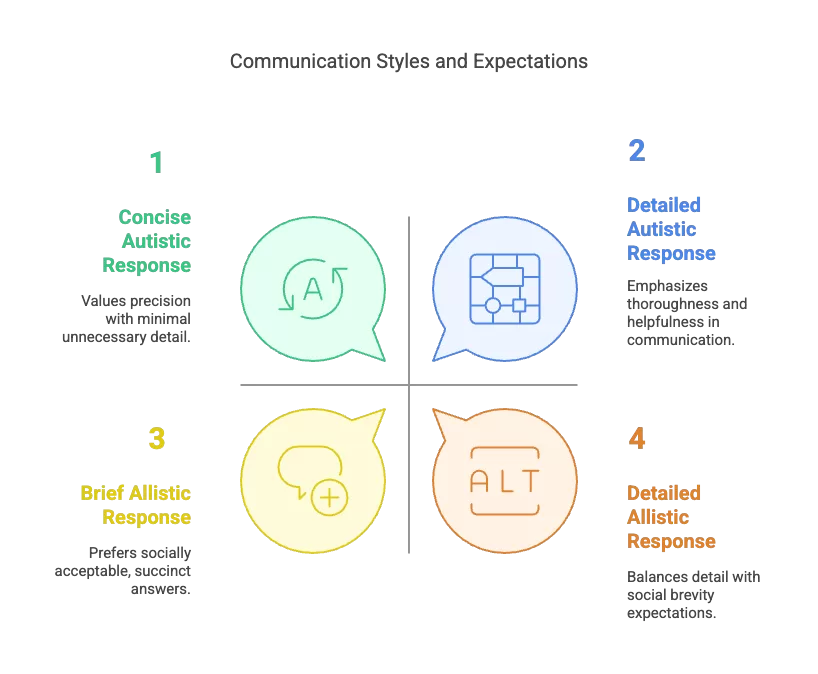

This maxim is about providing the right amount of information—not too much, not too little.

- Allistic people may expect brief, socially acceptable answers that balance detail and conciseness.

- Autistic individuals often value thoroughness and accuracy, sometimes providing more detail than allistics might expect. This is not “over-explaining” but rather an attempt to be precise and helpful.

Example: “Where is the nearest petrol station?”

Allistic: “It’s two blocks ahead on the left.”

Autistic: “It’s two blocks ahead on the left. If you’re looking for a cheaper option, there’s another one three blocks further, and that one has better reviews for customer service.”

Misinterpretation Risk: Allistic individuals might perceive the autistic response as excessive, while autistic individuals might feel frustrated by vague responses lacking useful details.

2. Maxim of Quality: Be Truthful

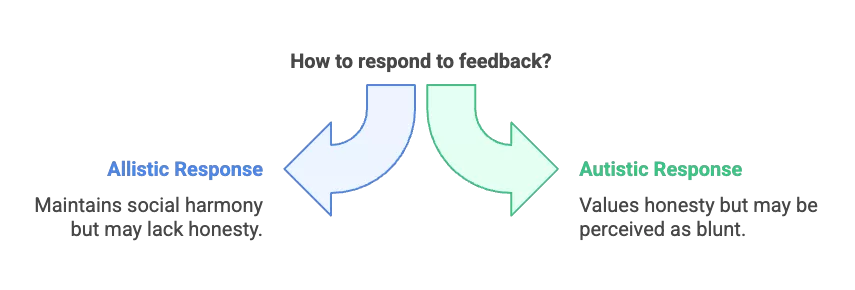

This maxim ensures that communication is honest and based on evidence.

- Allistic: White lies and social niceties are often used to maintain harmony.

- Autistic: Honesty is highly valued, often to a greater extent than social norms dictate.

Example: “Did you like my presentation?”

Allistic: “Yes, it was great!” (Even if they had some critiques)

Autistic: “It was well-structured, but I think the data visualisation could be clearer. Would you like some feedback?”

Misinterpretation Risk: Allistics might view this directness as “blunt” or “rude,” while autistic individuals might struggle with indirect or insincere responses.

3. Maxim of Relation: Be Relevant

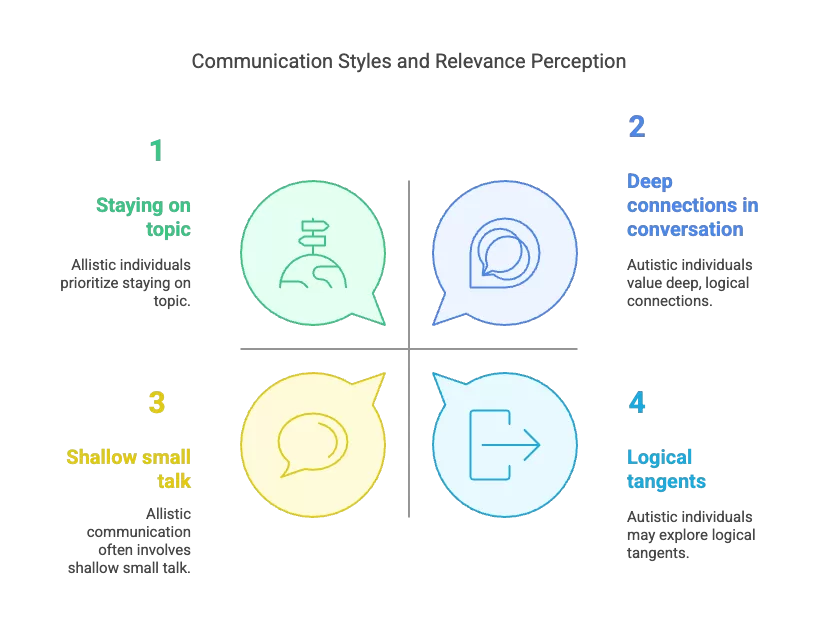

Contributions should be logically connected to the conversation.

- Allistic: Social cues often dictate what is considered “relevant.” There may be an expectation to stay “on topic” even if connections are abstract.

- Autistic: individuals may make deep or lateral connections that allistic listeners do not immediately see as relevant but are logical within their framework.

Example: “How was your weekend?”

Allistic: “It was great! I went hiking.”

Autistic: “It was great! I went hiking, which reminded me of a documentary about environmental conservation. Did you know deforestation has increased by 30% in the last decade?”

Misinterpretation Risk: Allistic individuals might see this as “going off on a tangent,” while autistic individuals might find small talk shallow or unengaging compared to deeper discussions.

4. Maxim of Manner: Be Clear

This maxim focuses on avoiding ambiguity and being organised in speech.

- Allistic Communication: Social conventions often allow for vague, implied meanings and indirect phrasing.

- Autistic Communication: Clarity and literal language are often prioritised, and indirect communication may be confusing or frustrating.

Example: “It’s lunchtime.”

Allistic: Understands this as asking if they would like to have lunch together.

Autistic: “Yes, it is.” Simply confirming the factual statement.

Misinterpretation Risk: Allistics may expect implied meanings to be understood without direct statements, while autistic individuals may prefer explicit wording to avoid misinterpretation.

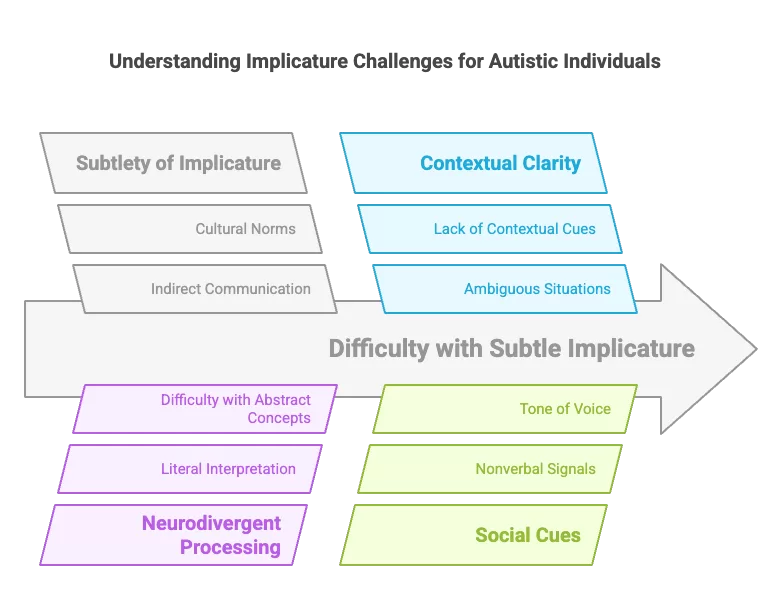

Flouting and Violating the Maxims Across Neurotypes

While people generally follow these maxims, they sometimes deliberately break them to imply hidden meanings (flouting) or deceive (violating). Different neurotypes may experience these violations differently.

Flouting a Maxim (Creating Implicature)

Speakers sometimes intentionally break a maxim to create an implied meaning (known as conversational implicature). If these implied meanings are too subtle, autistic individuals might struggle with them.

- Example (Flouting Quantity, Allistic Style):

- A: “How was the meeting?”

- B: “Well… everyone showed up.”

- (Implies the meeting was unproductive without directly saying so)

- Potential Autistic Response:

- A: “Does that mean it was a waste of time?”

- (Clarifies the implied meaning rather than assuming it)

Violating a Maxim (Misleading the Listener)

Unlike flouting, a violation is when someone intentionally misleads without signalling an alternative meaning. Autistic individuals may struggle with these violations as they often expect honesty.

Example (Violating Quality, Allistic Style):

- Q: “Did you submit the report?”

- A: “Yes, of course!” (But hasn’t submitted it)

- Potential Autistic Response: “Why did they say they submitted it when they didn’t?” (Difficulty understanding why someone would lie instead of just explaining the delay)

Why Understanding These Differences Matters

Recognising these differences in communication styles can help foster mutual understanding and inclusion:

- Allistic individuals can practice being more explicit, patient, and open to detail.

- Autistic individuals can advocate for clearer communication expectations in their social environments.

- Both groups can develop greater empathy for each other’s conversational styles.

By embracing these differences, we can create more accessible, effective, and meaningful communication for everyone.

A post I wrote in 2009, Maybe-No People, demonstrates where Maxim of Manner has been a problem for me, though I was unaware of the maxims. I don’t think that ‘maybe’ was used to put me off something as a kid until I forgot about it; I’m sure that there would have been times when ‘maybe’ became a ‘yes’ but maybe that was just when I was persistent.

Have you experienced these differences in communication? Share your thoughts below!

Leave a Reply